I. Seems like straw to me

The year is 1274, and we are in Priverno, Italy. A schoolman from Paris lies in Fossanova Abbey, sick, sick to the death. He himself is a Dominican, but the Cistercian brothers of Fossanova Abbey are nonetheless “delighted to receive so distinguished an inmate.”1 Word of the Parisian schoolmen had found its way to Italy long before the man did, and legends linger with the music from his mouth. He has reformed Philosophy as an academic discipline, he has reintroduced Aristotle into the academic schedule, he has proven every point of Theology through the use of Logic — the Cistercian brothers know this, all of Italy knows it, all the Church knows it. Pope Gregory X invited him specifically to discuss the disputes between the Roman and the Greek Church.2

Still, it all means nothing to him. “All that I have hitherto written seems to me nothing but straw,” he says.3 When asked for any wishes he had to express, he says that “soon he should have every wish gratified.”4 On March 7th, 1274, there in Fossanova Abbey, he shut his eyes to sleep for the last time. His name is St. Thomas Aquinas, declared by Pope Pius V to be the first official Doctor of the Church, and till this day there is equal to him.

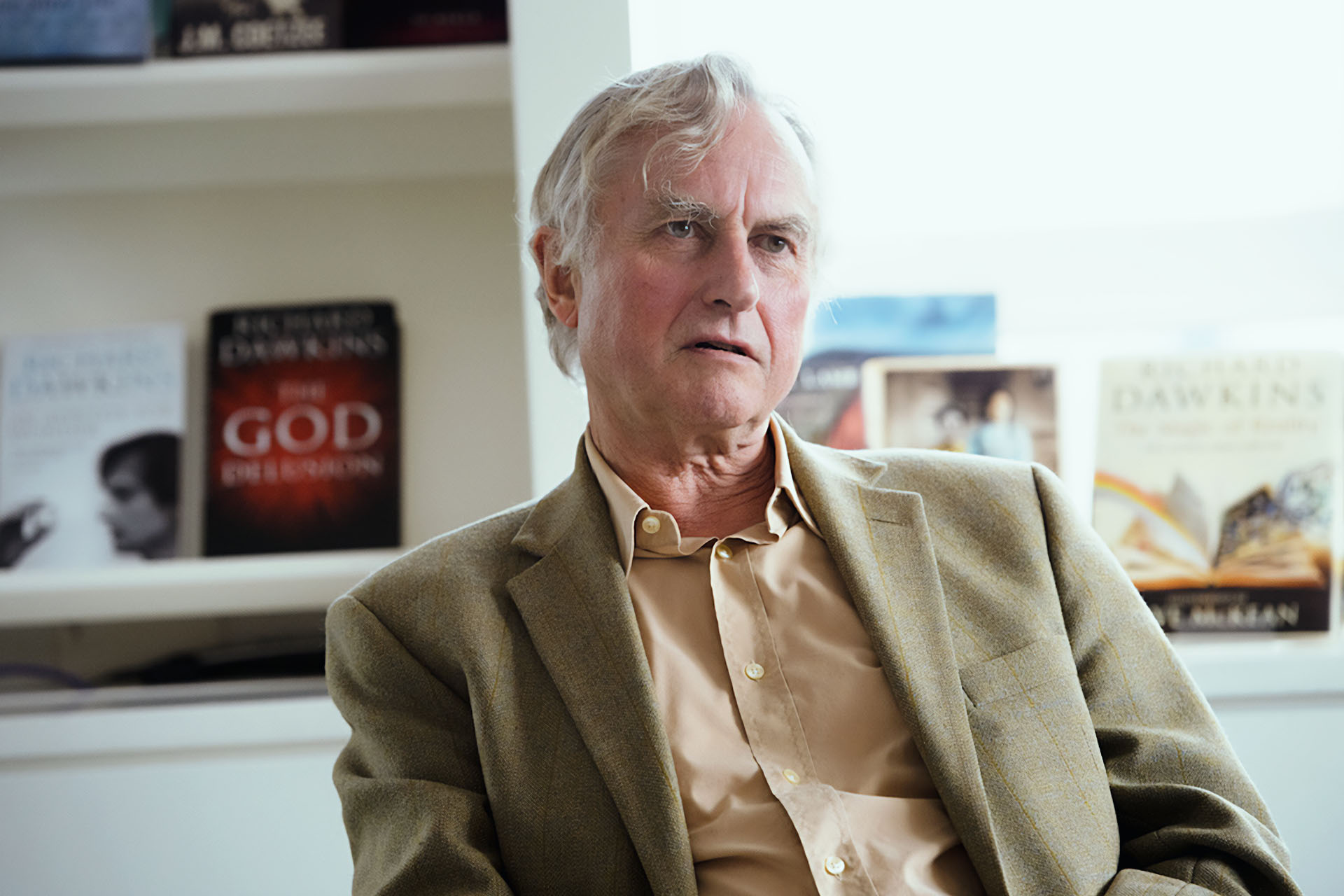

I thought of St. Thomas recently when I saw Richard Dawkins, now 83 years old, interviewed on LBC. In the interview, he said: “Well, I must say I was slightly horrified to hear that Ramadan is being promoted instead [of Christmas]. I do we think that we are culturally a Christian country. I call myself a cultural Christian.”5 This was Dawkins’ last contribution to public discourse. Or in other words, Dawkins’ last contribution was a surrender to the sword of Ramadan that is now “culturally” conquering his beloved Britain. This interview was published on YouTube on April 1st, 2024, so him thinking that being a confessed “cultural Christian” will ward off the Ramadan celebrations may have been an April Fools’ Day joke — and for Britain’s sake I hope it is. As of now, that video has over 138,000 views, which is about as much as Bishop Barron’s latest Sunday sermon, so a lot for an online atheist.

At the height of his career, Dawkins published his book The God Delusion, which ranked “at number five on America’s Amazon.com bestseller list,” at least according to an online article published by The Guardian, added to it the notification that “This article is more than 18 years old”6 — The God Delusion was published in 2006. Considering that this is his magnum opus, I read it. I read it, and I found no apologetics for atheism, but only struggling and bitter brawling with strawmen. I found misquotations, miscategorizations, and arguments so ailing that any Parisian schoolman there in the 13th century would have chuckled when reading it. But read it I did.

II. An Eerie Entry to The God Delusion

So I opened the book, The God Delusion. I did not read it cover-to-cover; I wanted to dive right in. Page 14 caught my eye: Dawkins here mentions “epistemological differences between [Thomas] Aquinas and Duns Scotus.” Duns Scotus, being one of the vanguards of medieval philosophy, is, of course, immediately dismissed as Dawkins “need consider only those theologians who take seriously the possibility that God does not exist and argue that he does,”7 an excuse as good as the ones I have heard from the Philosophy students in Mainz and Bingen who did not do their homework. We will later see what becomes of Thomas Aquinas. On page 15, he says that “to the vast majority of believers around the world, religion all too closely resembles what you hear from the likes of [Pat] Robertson, [Jerry] Falwell or [Ted] Haggard, Osama bin Laden or the Ayatollah Khomeini. These are not straw men, they are all too influential, and everybody in the modern world has to deal with them.”8 Who? Because I — a Chinese migrant in Europe — only know Osama bin Laden who was dealt with by U.S. President Obama. It is a pity that the British television did not provide Dawkins with enough examples from “around the world.” This double page, page 14 and 15, already gives the sensible mind an idea of what sort of manuscript is here being sold.

Perhaps I just picked a bad example. So let us read a chapter instead; and take chapter 3, because I like the number 3 for religious reasons. The chapter begins with an epigraph quoting a U.S. founding father saying: “A professorship of theology should have no place in our institution. Thomas Jefferson.”9 Very punchy. Sadly, and to my surprise, there is no reference, surprise because Dawkins worked as a professor at the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008, so I expected him to have the academic etiquette. Instead, I researched the reference myself and, lo and behold, found the full quotation from Thomas Jefferson’s letter to Thomas Cooper on October 7th, 1814: “I agree with yours of the 22d that a professorship of Theology should have no place in our institution. but we cannot always do what is absolutely best. those with whom we act, entertaining different views, have the power and the right of carrying practice.”10 So it was not Thomas Jefferson who said that “a professorship of theology should have no place in our institution,” but Thomas Cooper; and Jefferson’s practical response to it was that “we cannot always do what is absolutely best,” and “those … entertaining different views have the power and the right of carrying practice.” How unlucky for Dawkins — a professor at Oxford — that he misread that, and afterward forgot to provide a reference — which of all students at Oxford is expected. But perhaps the professor has outgrown the shabby habits of honourable scholarship. And how unlucky, too, that he could not find a quotation that actually agreed with him; such as this one by U.S President Ulysses S. Grant from his 1875 speech in Iowa: “Encourage free schools, and resolve that not one dollar of money appropriated to their support, no matter how raised, shall be appropriated to the support of any sectarian school. … Leave the matter of religion to the family circle, the church, and the private school, supported entirely by private contribution.” And the next sentence is even better: “Keep the Church and State forever separate.”11 Thomas Jefferson is cited for the epigraph of chapter 4 again,12 so replacing at least the epigraph of chapter 3 would have given it some variety. You are most welcome, Richard.

III. The Great Confusion of the Categories

Afterward, we hear of the name Thomas Aquinas again, as Dawkins refers to Thomas Aquinas’ “proofs,” which he, too, puts in quotation marks.13 These “proofs” are the Five Ways put forth by Thomas Aquinas in the first part of his Summa Theologicae, an enormous work of philosophy that, in the 13th century, properly introduced our universities to the Aristotelian principles it adopted from Arabic philosophers.14 In it, Thomas Aquinas says: “I answer that, The existence of God can be proved in five ways,”15 and then proceeds with his proofs. Dawkins says that “the first three are just different ways of saying the same thing”16 — but he is, unfortunately, mistaken. Firstly, Dawkins does not cite from the Summa Theologicae directly which is, again, no good sportsmanship, and, as we have seen with Thomas Jefferson, tends to fall to his advantage. Secondly, he summarizes the first two proofs in this way: “1. The Unmoved Mover. Nothing moves without a prior mover. This leads us to regress, from which the only escape is God. Something had to make the first move, and that something we call God. 2. The Uncaused Cause. Nothing is caused by itself. Every effect has a prior cause, and again we are pushed back into regress. This has to be terminated by a first cause, which we call God.”17 Dawkins is right to say that “these arguments rely upon the idea of a regress and invoke God to terminate it,”18 but cause and movement are two distinctly different things; just as entropy and temperature, though related, are not the same. To “cause” something or to “move” something are not the same: to cause chaos is to be chaotic, but to move chaos is to try manage it.

The third proof is summarized by Dawkins in this way: “3. The Cosmological Argument. There must have been a time when no physical things existed. But, since physical things exist now, there must have been something non-physical to bring them into existence, and that something we call God.”19 Dawkins tries to refute all three proofs together — a courageous feat, if we were to not call it naive — upon their shared “idea of a regress.”20 But that “regress” is a method used not only in theology and philosophy, but also in physics and biology — “to conjure up, say, a ‘big bang singularity,’”21 or in Charles Darwin’s evolution theory,22 both of which are in The God Delusion discussed —, need, I hope, not be mentioned. Now, a Philosophy student might say that one is metaphysical regress while the other is physical regress, and that is correct — we will discuss their difference right now.

Dawkins cites a “Karen Owens” by suggesting that an “omniscient God” would have “the omnipotence to change His future mind.”23 This is what Immanuel Kant called a “Dialectical Illusion,”24 because it applies natural principles — such as changing one’s mind — to a transcendental idea. The transcendental mind is defined as “omniscient” and “omnipotent,” so the principles of a natural mind, which is neither omniscient nor omnipotent, do per definition not apply. Or in other words, Dawkins is confusing these two categories, the physical and the metaphysical, to make a point. The same Dialectical Illusion is initiated when Dawkins says that “it is by no means clear that God provides a natural terminator to the regresses of Aquinas.”25 The word “natural” should have no place here, because in all three proofs, Thomas Aquinas defines God as transcendental, not natural. God, according to Dawkins’ own paraphrase, is “The Unmoved Mover,” ”The Uncaused Cause,” and “something non-physical.” It is, therefore, and contrary to Dawkins, quite clear that God provides no “natural terminator to the regresses of Aquinas,” because God is not natural. Instead, transcendental terminators are provided, two of which Dawkins mentions: that God is “omniscient” and “omnipotent,” terminators which we do not find in our natural world, hence they are transcendental. Physics and Metaphysics are not the same. Dawkins is running in circles by confusing categories.

And he continues doing this to Thomas Aquinas’ fourth proof: “4. The Argument from Degree. We notice that things in the world differ. There are degrees of, say, goodness or perfection. But we judge these degrees only by comparison with a maximum. Humans can be both good and bad, so the maximum goodness cannot rest in us. Therefore there must be some other maximum to set the standard for perfection, and we call that maximum God.”26 Dawkins refutes this by saying that “people vary in smelliness, but we can make the comparison only by reference to a perfect maximum of conceivable smelliness. Therefore there must exist a … peerless stinker, and we call him God.”27 Besides the childishly crude reductionism, once again, the categories of natural and transcendental are confused. “Goodness or perfection,” or as Thomas Aquinas put it, the “good, true, noble, and the like,”28 are transcendental qualities. Or in other words, they are abstract. “Smelliness” is not abstract, but instead very sensible, or in another word, natural. Now, these two categories might seem like made-up concepts, but they apply to our modern sciences too. Numbers, for example, are abstract and transcendental. That is why students struggle to understand and use them. You do not see 2’s and 37’s running around and about in the same way you would see plants or animals, because one is transcendental, while the other is natural. That is why you cannot measure numbers in the same manner you measure plants or animals, because you have to consider their categories. Even within the same category of, say, biology — Dawkins is a biologist, I should add —, plants and animals are distinctly different subcategories, and therefore require distinctly different scrutiny.

IV. Can’t do it Like Kant

Dawkins’ refutations, so far, are so pathetic that I feel I must myself provide a proper refutation of my own position. Let us, therefore, look again at the distinct differences between the natural and the transcendental, which, apparently, Thomas Aquinas’ first three or four proofs rely upon. He defines God as, and I cite from the Summa Theologicae directly, “a First Mover,” “a First Efficient Cause,” and “some being having of itself its own necessity.”29 All these are transcendental qualities, so consider the category here. Now, a philosopher might object to this that human reason, or in other words, the natural mind, cannot move from the natural to the transcendental since it is not a transcendental mind, which renders Thomas Aquinas’ proofs impossible. Or in other words, how do you, with pure reason alone, imagine the maximum of the “good, true, noble, and the like,”30 or the maximum of “goodness and perfection”?31 It is impossible to imagine. That is why pure reason does not suffice to formulate a proof of God’s existence here, because such a proof is, from pure reason at least, inscrutable. This is, very roughly, how Immanuel Kant objected to it in his Critique of Pure Reason.32 He said that “the transcendental object lying at the basis of [natural] appearances … is and remains for us inscrutable.” He calls it a “Dialectical Illusion,”33 because “the concept of necessity is only to be found in our [human] reason, as a formal condition of thought; it does not allow of being hypostatised as a material condition of existence.”34 Or in other words, just because something needs to necessarily exist, does not mean it exists — that is why God’s existence cannot be proven from necessity. This is how you properly disprove Thomas Aquinas. You are most welcome, Richard.

We have now moved merely three pages into chapter 3 of The God Delusion, and Dawkins, already, has misquoted Thomas Jefferson, and confused the very categories he himself paraphrased. I begin to wonder whether only these three pages are Dialectical Illusion, or whether the entire book is. Perhaps, before anyone bothers to find out, why not read a better and more rewarding book instead — such as the King James Bible? And this recommendation is drawn directly from Dawkins, who in 2012 said in The Guardian: “A native speaker of English who has never read a word of the King James Bible is verging on the barbarian.”35 So surely, a reading of the King James Bible must be more rewarding than the pseudo-philosophical prowess-less pity that is The God Delusion.

Is this what Richard Dawkins wasted so many decades on? Why did he not continue his studies in Biology? Why waste such brilliance? Whereas St. Thomas’s last years were marked by a schoolman transcending his own studies, Dawkins’ twilight is marked by a sort of surrender, and a nagging nostalgia for the Christian culture he helped to destroy. At 83, Dawkins has become a prisoner of his own polemics. St. Thomas Aquinas was to be remembered for centuries as one of the greatest theologians of all time. Richard Dawkins, as the LBC interview foreshadows, will be remembered as an angry old man who let his alacrity for atheism contaminate everything he did.

So to Dawkins, there is only one thing left to say, for which I wish to cite again the words of Thomas Jefferson: “truth advances, & error recedes step by step only.”36 Now, attacking religion shall advance, and Richard, you shall recede. Death of the God delusion? Nay, death of The God Delusion!

*

* *

Signed Mannheim, October 20th, 2025. Published January 28th, 2026, the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas.

- Hampden, Renn Dickson, The Life of Thomas Aquinas: A Dissertation of the Scholastic Philosoph of the Middle Ages (London: John J. Griffin & Co., 1848), 47. ↩︎

- Ibid. 46. ↩︎

- Martin, Reis, “When the Words Stopped,” National Catholic Register, Mar 31, 2022, www.ncregister.com/blog/when-the-words-stopped (accessed Dec 6, 2025). ↩︎

- Hampden, The Life of Thomas Aquinas, 47. ↩︎

- LBC, “Richard Dawkins: I’m a Cultural Christian,” Apr 1, 2024, 8:10, www.youtube.com/watch?v=COHgEFUFWyg (accessed Oct 19, 2025). ↩︎

- Jamie Doward, “Atheists top book charts by deconstructing God,” The Guardian, Oct 29, 2006, www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/oct/29/books.religion (accessed Oct 19, 2025). ↩︎

- Dawkins, Richard, The God Delusion (London: Black Swan, 2006), 14. ↩︎

- Ibid. 15. ↩︎

- Ibid. 100. ↩︎

- Looney, J. Jefferson, ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, Vol. 8, 1 October 1814 to 31 August 1815, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 12–13. ↩︎

- Society of the Army of the Tennessee, Report of the Proceedings of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee, at the Sixth Annual Meeting, held at Madison Wisconsin, July 3rd and 4th, 1872 (Cincinnati: Society of the Army of the Tennessee, 1877), 385. ↩︎

- Dawkins, God Delusion, 137. ↩︎

- Ibid. 100. ↩︎

- Such as his Aristotelian opponent Averroes. See Rickaby, Joseph, Scholasticism (London: Archibald Constable & Co., Ltd., 1908), 34–39. ↩︎

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Part 1, First Number, QQ. I.-XXVI., trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (London: R. & T. Washbourne, Ltd., 1911), 24. ↩︎

- Dawkins, God Delusion, 100. ↩︎

- Ibid. 100–101. ↩︎

- Ibid. 101. ↩︎

- Ibid. 101. ↩︎

- Ibid. 101. ↩︎

- Ibid. 100. ↩︎

- Ibid. 103. ↩︎

- Ibid. 101. ↩︎

- See Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp Smith, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1929), 514. ↩︎

- Dawkins, God Delusion, 102. ↩︎

- Ibid. 101. ↩︎

- Ibid. 101. ↩︎

- Aquinas, Summa Theologicae, Part 1, 26. ↩︎

- Ibid. 25–26. ↩︎

- Ibid. 26. ↩︎

- Dawkins, God Delusion, 101. ↩︎

- Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, 508, 511–518. ↩︎

- Ibid. 514. ↩︎

- Ibid. 518. ↩︎

- Dawkins, Richard, “Why I want all our children to read the King James Bible,” The Guardian, May 19, 2012, www.theguardian.com/science/2012/may/19/richard-dawkins-king-james-bible (accessed Oct 19, 2025). ↩︎

- Looney, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, Vol. 8, 12–13. ↩︎